Nowadays, one no longer goes to the asylum, one founds cubism.

Being one of the most famous artistic movements of the 20th century, cubism is the result of the collaboration and friendship between Pablo Picasso and Georges Braque. Strongly influenced by the painting of Paul Cézanne, as well as by African art, Picasso embarked on this path following a reflection he had been contemplating for some time. So how did Picasso arrive at cubism? How is cubism characterized?

The beginnings of cubism

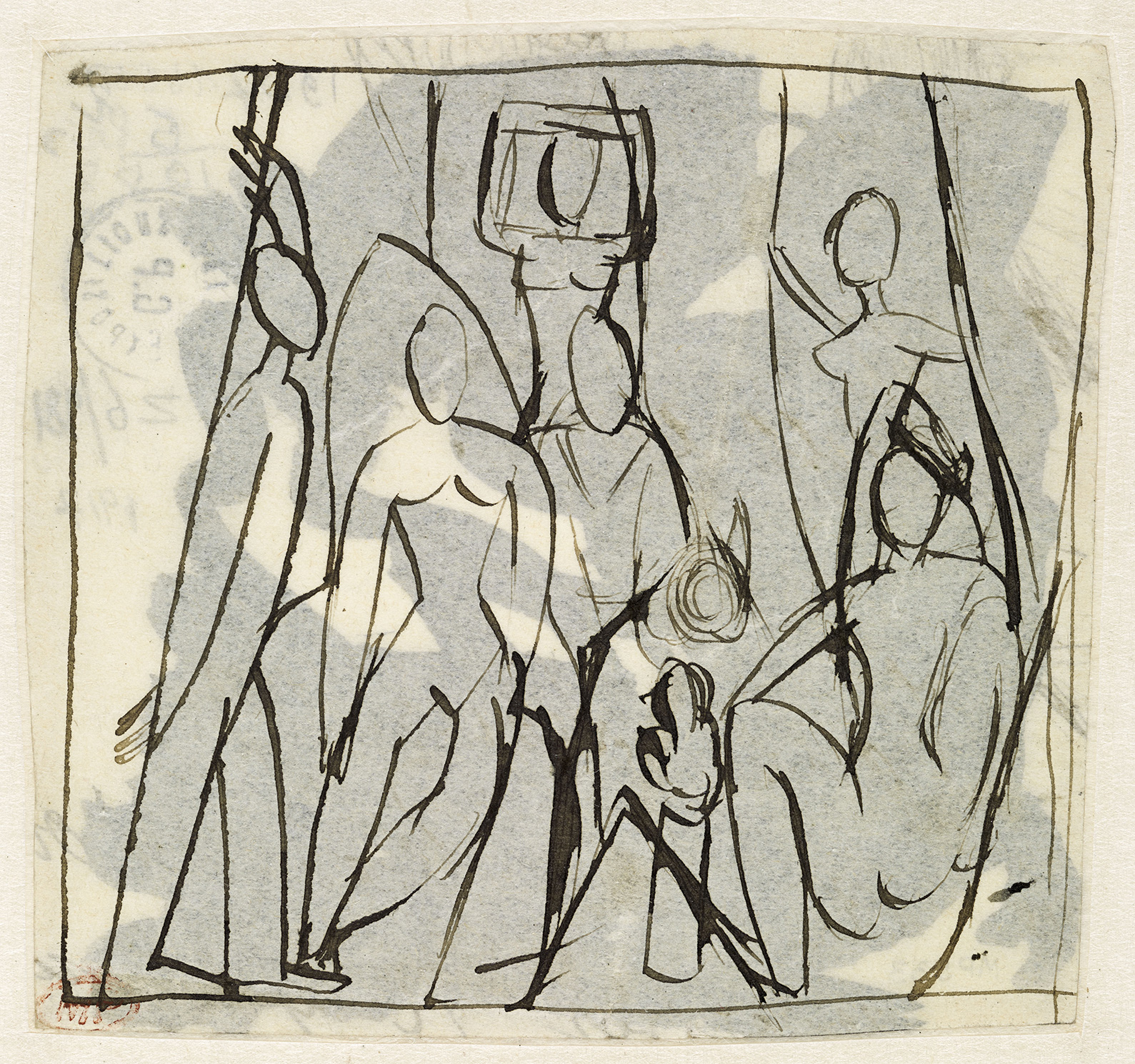

During the winter of 1906, Picasso began preparatory studies for what would the following year become "Les Demoiselles d'Avignon" (Museum of Modern Art, New York).In addition to showing the viewerIn addition to showing prostitutes (the Rue d'Avignon being a place of prostitution in Barcelona), the pictorial representation of Les Demoiselles shocked the public of the time. From its creation until its exhibition at the Salon d'Antin in Paris in 1916, the work alternately aroused indifference, incomprehension, or rejection both because of its subject and its treatment. Here indeed, the perspective is modified (the faces are frontal and the noses in profile for example), the bodies are stretched and strongly stylized. There is already a desire to geometrize reality and the models.

At the same time, Picasso admired and was inspired by the works of Paul Cézanne (1839-1906), who left an artistic legacy that influenced many painters during the retrospective devoted to him at the 1907 Autumn Salon. Although they never met during their lifetime, Cézanne and Picasso shared the same conception of painting as visual transposition. Over the months, Pablo followed to the letter his elder's lesson of geometric volumes: "Treat nature by the cylinder, the sphere, the cone, all in perspective.”

Picasso and Braque

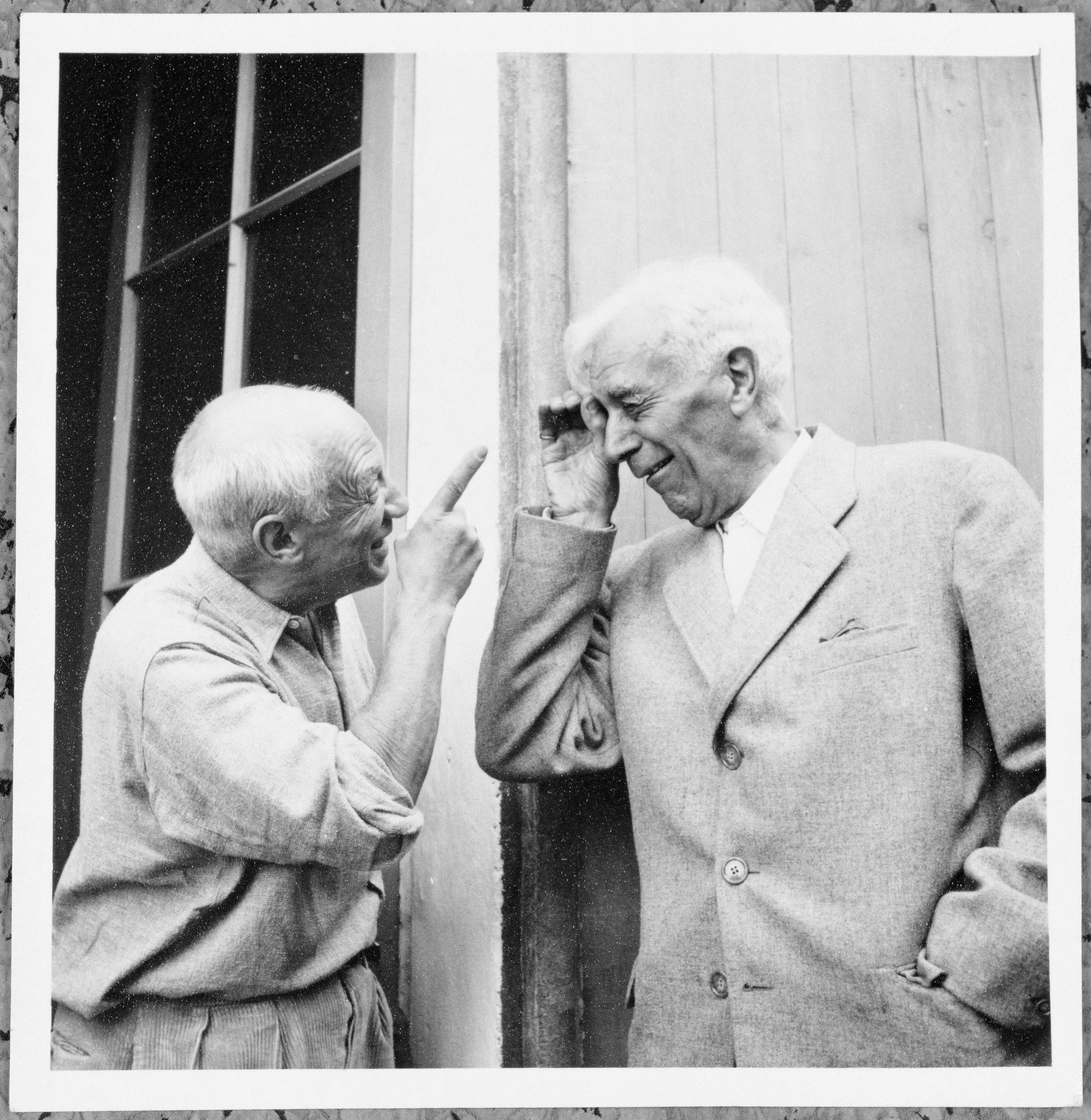

In November 1907, Guillaume Apollinaire, poet and close friend of Picasso, organized a meeting with Georges Braque, a young painter who was part of the Fauve movement. "Les Demoiselles d'Avignon", barely finished, could be seen in a corner of the Bateau-Lavoir studio that Picasso had occupied in Montmartre since 1904. Braque could not believe it: "Your painting is as if you wanted us to eat oakum or drink petrol". Following this first meeting, Braque invited Picasso to his own studio, also located in Montmartre. It was the Spaniard's turn to discover Braque's work. He admired the landscapes painted in the south of France, in l'Estaque, where Braque regularly went. A bond was created between the two artists and from that moment on, they worked side by side to develop an extremely powerful pictorial dialogue. They remained friends for a long time, even years later, when Picasso put cubism aside for other artistic adventures.

Analytical Cubism

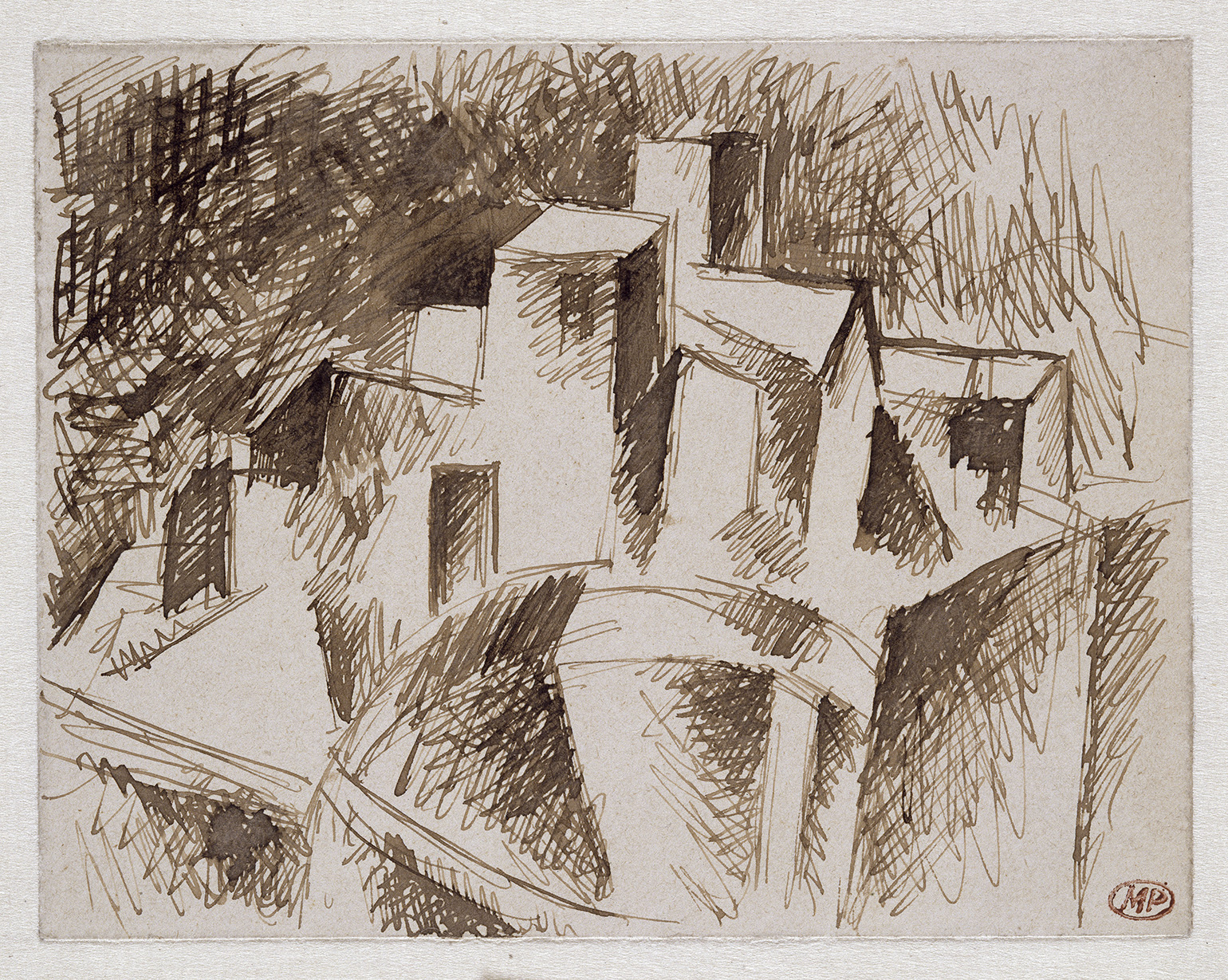

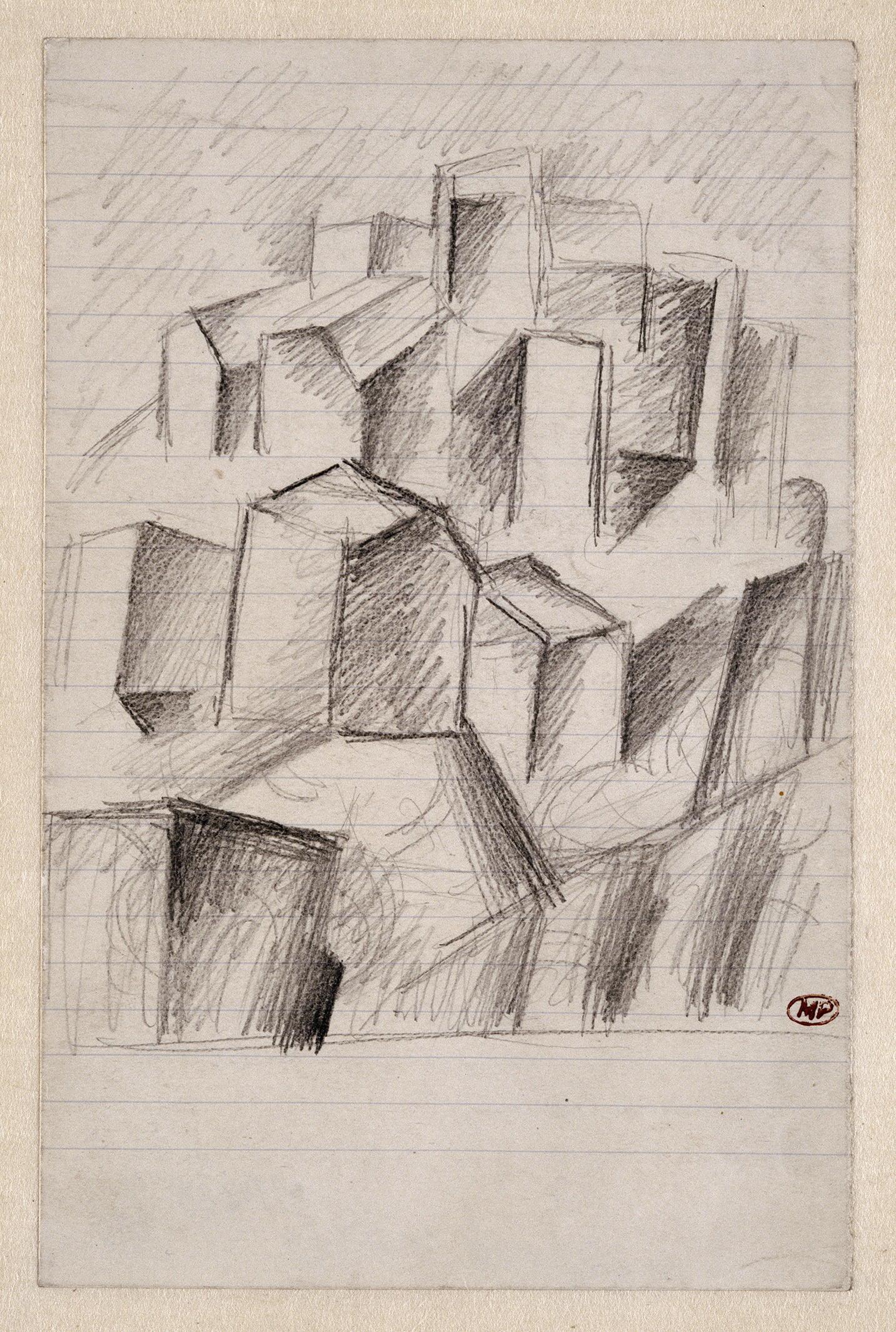

In 1909, Picasso spent the summer in Horta, the village of his friend Pallarès, located in southern Catalonia, and deepened his new way of painting. In his drawings as well as in his paintings, the small village becomes a mixture of cubic forms, intertwined with each other.

Little by little, and until 1912, Cubism takes more and more distance from the subject represented. This is called "analytical" cubism. This results in a fragmented and almost monochromatic representation of the subject. The forms are defined by cubes, rectangles and cylinders whose facets interpenetrate, which often makes them difficult to decipher.

Cubism quickly imposed itself by its strength of representation. Other painters, such as Juan Gris, Fernand Léger, Jean Metzinger or Francis Picabia, did not fail to adopt this new visual language. Unlike Picasso and Braque, who refused to exhibit their works, they were the ones who promoted the movement to the general public. The 1911 Salon des Indépendants brought together their works in the same room.

Synthetic Cubism

In 1912, in order to escape the limits of analytical cubism and reaffirm a more visible link with reality, Picasso introduced elements of everyday life into his works. He thus initiated a new aesthetic reflection on the different levels of reference to reality: this is the so-called "synthetic" cubism. Picasso was in Le Havre with Braque when they began to insert stenciled lettering into their works, as well as organic materials, such as sand. Picasso then created the first collage in the history of art, "Still-Life with Chair Caning", in Paris in the spring.

The collage is characterized by an unprecedented juxtaposition of elements that are not only representation, but also simple presentation. In addition to the painted signs that summon fragments of newspaper, pipe, glass, lemon slice, knife and scallop, Picasso introduces a piece of reality by gluing on the canvas a piece of oilcloth imitating a chair cane and by girdling his oval composition with a rope. A few months later, he continued in this vein by inventing papier collés, which regularly resorted to the use of newspaper. The height of Cubism occurred in the fall of 1912, with the exhibition of the Golden Section in the Parisian gallery of La Boétie. The event brought together some thirty artists, including Albert Gleizes (1881-1953) and Jean Metzinger (1883-1956), and saw the publication of a treatise, "On Cubism". This reference book traces visual art back to Gustave Courbet, explaining that cubism is a logical artistic development with innovative aspects.

The shock of the War

The First World War, in 1914, brutally interrupts the rise of cubism. Many artists were enlisted, including Braque and Derain. Picasso, of Spanish nationality, was not called up, but in Paris, he reoriented his work and gradually reintroduced a classical representation of the subject before embarking, in 1917, on the collaborative adventure of the Ballets Russes. On his return from the trenches, Braque was wounded and did not paint again until 1917.